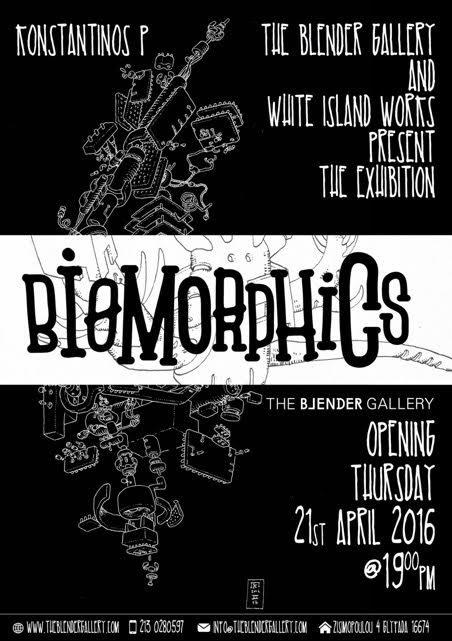

Biomorphics by Konstantinos Papamichalopoulos

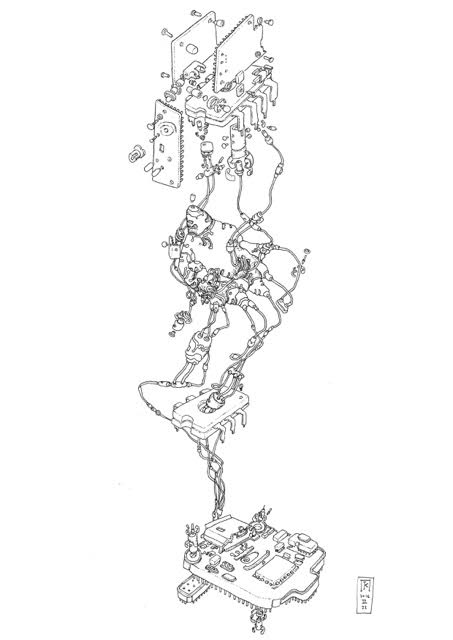

The creation of a bionic man, in a universe where technology and human experience go hand in hand, forms an important point of reference in the art of Konstantinos Papamichalopoulos. In his visual narrative on linking man and machine the artist illustrates for Blender his Biomorphics, a “notebook of drawings” that form the original idea, the vehicle to capture the cellular structure that attempts to reconstruct man, to make him something more than a man.

From Talos and Golem to the medieval puppets, phantasy mythology has documented infinite attempts of man to create in his image the absolute anthropomorphic machine. Fascination with creation that transforms man to creator has been captured in classic literature, with the characteristic example of Frankenstein by Mary Shelley, in cinema with the emblematic robot in “Metropolis” by Fritz Lang and in our days in the culture of comics and videogames.

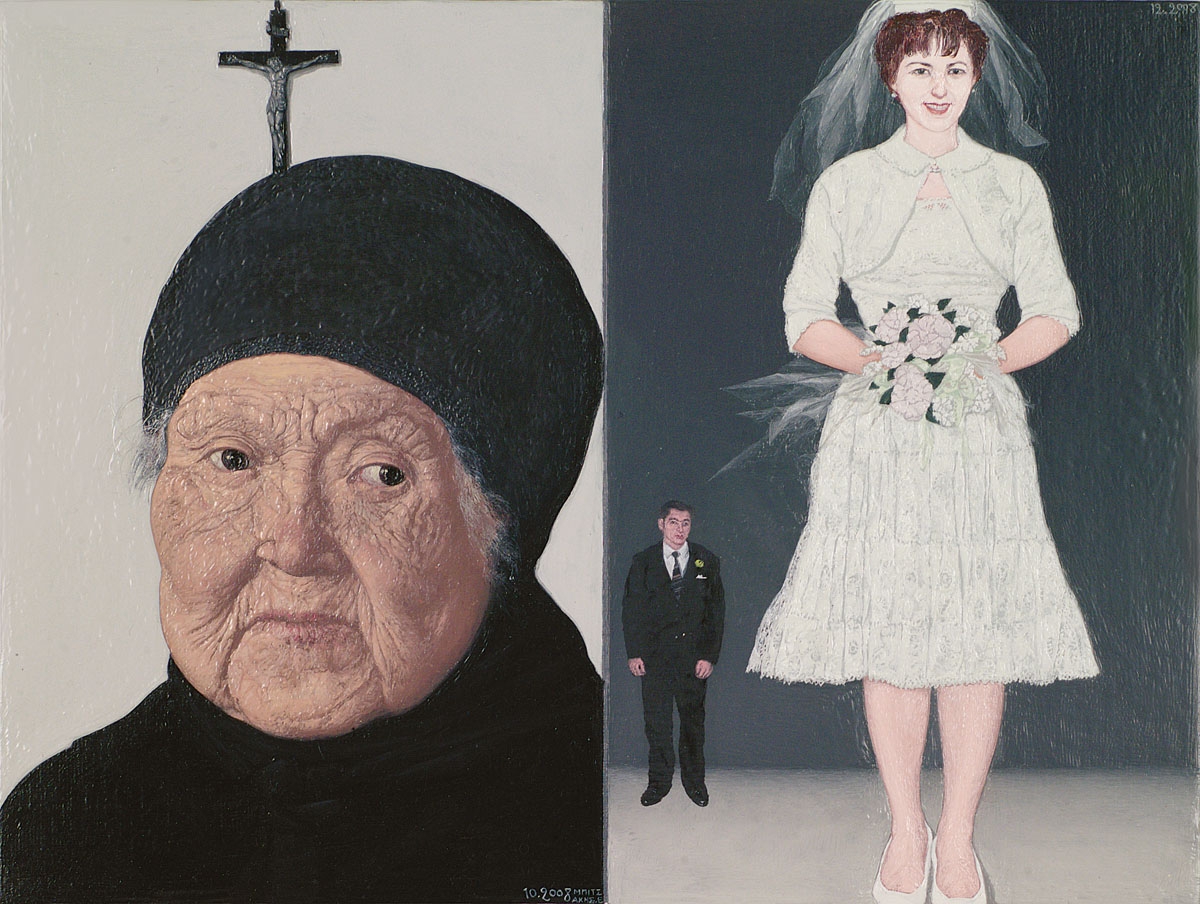

Such love for comics and videogames was of a great influence for the artistic development of Papamichalopoulos. In comics and in videogames he discovered a huge visual world. Just as the videogames do not care to “look” like paintings or to reproduce a coherent world, so too the artist did not want to resort to a conventional portrait painting, to a portrayal of a cohesive world. He consciously immersed himself in the creation of a web without boundaries that brought together comics, painting, engraving, design and digital applications.

The exhibition constitutes a study on the graphisms that Papamichalopoulos developed in his first comic, entitled “The Japanese”, in 2000 (the third version of the successful album has just been published). Such kind of “graphisms”, as the author himself calls them, are a recurring theme in his work, even before 2000. Frank Miller and his comic “Ronin” - more specifically the pieces that formed the artificial part of the main character - have been of a foremost influence. In a similar way to Miller, Papamichalopoulos does not limit himself to a narrative that simply results in the creation of a comic. Equipped with an inquiring look and a solid knowledge of the history of art, the Greek artist attempts a unique combination and integrates organically into his own universe the stylistic aftermath of Oriental art – the art of Hokusai and Hiroshi – together with the “Westerner” Yves Tanguy and Jean Dubuffet, affording to his work a greater depth.

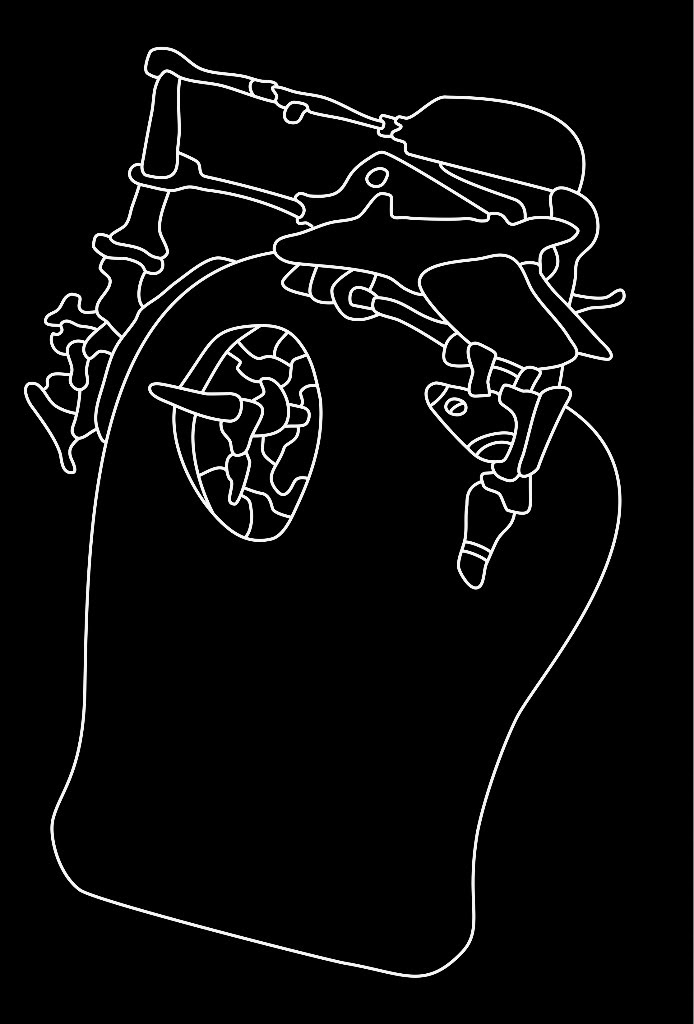

Biomorphics bring in mind multicellular organisms under a microscope, a series of cellular structures that unfold a kind of formulation. Papamichalopoulos visually transcribes the perception of digital world on the internet, which is not a linear process, but an inexhaustible world that is constantly recreated out of hypertexts, superimposed unions of unions, infinite connotations. In his painting technology comes first. “Technologies that man himself creates in order to make the world surrounding him work is something natural. Pencil or paper, oil paints or temperas are exactly that: technologies. The term “technology of materials” that was in use much before the invention of computers is not accidental at all. For example, in the 14th century engraving was the last word in technical creation, reproducibility and dissemination of a work of art. In the 21st century iPhone, iPad, operating systems, PlayStation & Xbox, Unity and other similar platforms are inevitably considered as the state of the art. I like the fact that art is a technical construction and I use it in order to understand the world around me”. And despite the influence of video games culture, manga and animation, Papamichalopoulos proceeds in a constant process of abstraction.

It is his belief that we understand our experiences through the acceptance of a fragmented world, through “screens” and “fragments”, in the same way that someone stands in front of an ancient statue with broken limbs. Such reconstruction of a world through piece and fragment plays a pivotal role in the coexistence of the many legitimate variants of the experience.

Following the same logic as in the set-up of the Great Golden Room (Museum of Greek Folk Art 2015), in Blender the author does not follow the traditional logic of artworks’ set-up, i.e. a passing on the surface of the wall. He attempts a work as a whole: he creates a fragmented body, the head elsewhere and a different frame beneath, where the torso has its own autonomy and is a work within the work. Whole houses, like birds that emerge suddenly, a small work like a biomorphic cell and a little further on a hand, a study of a hand, and this as a whole setting up a whole body out of fragmented “experiences” of the body. Artemis Lydi conceived and designed elaborate components – “armours” and necklaces – creating the series of black biomorphic and transferring in practice, i.e. in the body itself, the rationale and motives of Papamichalopoulos. In a playful mood, in the same manner as the surrealists set up their toys, in Blender a universe is presented, made out of various materials and different articulation of space, based on the “multimedia” experience we have for the world, through parallel screens, television, iPad, mobile phone.

What interests the author is each work having micro-narratives within it, which compose a whole world in each work. Consecutive events create narratives for each other. The viewer retains his free will to decide in front of which work he wants to stand and on which point he wants to focus. Biomorphics do not merely compose an endless collage of fragments, but in essence they also call us to revisit painting through digital experience.

“It is only human to recognise that our abilities are limited and we need constantly to break our limits in order to move a little bit forward. And this is done through multiple narratives. We do not share a coherent narrative that unites us, but rather a rootstock, without beginning or end, and each of us finds his own outlets. That’s the way I want people to view my painting; it does not have only one reading, there isn’t only one true, there isn’t only one way to look at a work”.